Faith

Having been personally involved in the advocacy for the 1986 legalization law during my tenure as executive director of the U.S. Bishops' Migration Committee, I know that bipartisan action is very necessary.

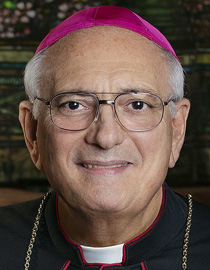

DiMarzio

Deportation is often seen as a last resort in enforcing immigration laws. It is not considered a punishment but rather an exercise of a government's sovereign right to exclude from its nation whomever its laws dictate. More common are expulsions, which occur at ports of entry, such as land entrances or airports. Deportation is the removal of criminal aliens or, at times, those who have exceeded their visa time or are present in the country without permission. Usually, voluntary departure is presented as the first option.

However, some distinctions need to be made regarding criminal aliens who have committed felony offenses, such as drug trafficking, theft, or violent crimes, including sex crimes.

Misdemeanors are not normally considered a reason for deportation because immigration laws are civil offenses and are treated differently. However, people who are undocumented or even those with legal status can be deported for some criminal misdemeanor offenses.

The new presidential administration has promised to pursue the mass deportation of the estimated 11-12 million undocumented people in our country. The deportation of criminal aliens who have committed and been convicted of felonies and are a threat to communities is a logical fulfillment of immigration law. However, the issue of almost indiscriminate deportation, which may include families with mixed legal status -- with some American-born or permanent residents -- is quite another issue.

In the 1980s, our country faced a situation similar to today, with about 3-5 million undocumented persons. A solution was found, however, in granting permanent residency to those who fulfilled certain conditions of residence and good comportment. If this program had been more inclusive, it would not have left a residual of undocumented persons who contributed to our present situation.

Also, the full implementation of employer sanctions for hiring undocumented persons was never fully enforced. Undocumented status is not good for people and not good for our country. A solution was once found and could be applied again with a better understanding of the economic value of immigrants, as well as the moral and social implications of expelling potential citizens.

Sometimes, comparative analysis clarifies conceptual problems. If I were to use the words amnesty or even legalization, which were used in 1986 legalization, few would listen. However, an example from Italy, which deals with many undocumented persons given the thousands of miles of open seacoast, is their periodical issuance of a "sanatoria" -- the healing of the presence of undocumented persons. This recognizes their contribution to their country. A similar approach in the U.S. has been used in the past. The registry provision in U.S. immigration law has never promoted "a get-off-free approach."

Rather, it is one based on social equity and common sense. If people are working, self-sufficient, paying taxes, or even contributing to Social Security, they should be given an opportunity to remain. This provision of the law was introduced in 1929, and the most recent registry date is in 1972. If the date were to be advanced to 2010, it is estimated that 6.8 million could be legalized. This would be more beneficial to our country and less expensive.

In the past, when restrictions were placed on immigration, it normally came from the philosophy of isolationism. After World War I, many Americans believed that involvement with the rest of the world was not necessary, and a very restrictive and racist Immigration Act of 1924 (also known as the Johnson-Reed Act) was passed. In today's globalized world, however, it is almost impossible to survive in an isolationist mode regarding trade and migration. The world has become interdependent. Physical barriers do little to stop migration, given that all social and economic forces foster it.

Before we turn to massive deportation programs, which are not only very costly but also very disruptive to society and especially family unity, perhaps a program to heal the wound of undocumented migration in our country should be attempted. Having been personally involved in the advocacy for the 1986 legalization law during my tenure as executive director of the U.S. Bishops' Migration Committee, I know that bipartisan action is very necessary.

In the 1970s, I also witnessed the raids on workplaces, which resulted in physical harm to both aliens and immigrant workers. In their attempt to escape workplaces, many were injured by jumping out of windows. In addition, enforcement personnel were placed in untenable situations and dangerous situations in workplaces by attempting to pursue and arrest workers.

Certainly, the United States is capable of a more thoughtful and civilized approach to dealing with migration than the mass deportations of immigrants and their families, who contribute to our national well-being.

Catholics and others of goodwill should oppose this plan and promote the legalization and integration of immigrants who continue to contribute to our nation.

- Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio is retired bishop of the Diocese of Brooklyn, N.Y. He writes the column "Walking With Migrants" for Catholic News Service and The Tablet.

Recent articles in the Faith & Family section

-

Presentation of the LordFather Robert M. O'Grady

-

Life is beautifulArchbishop Richard G. Henning

-

Faith to Rebuild in PakistanMaureen Crowley Heil

-

Scripture Reflection for Jan. 26, 2025, Third Sunday in Ordinary TimeFather Joshua J. Whitfield

-

Why you should visit a monasteryDr. R. Jared Staudt