The Healy daughters and sisters

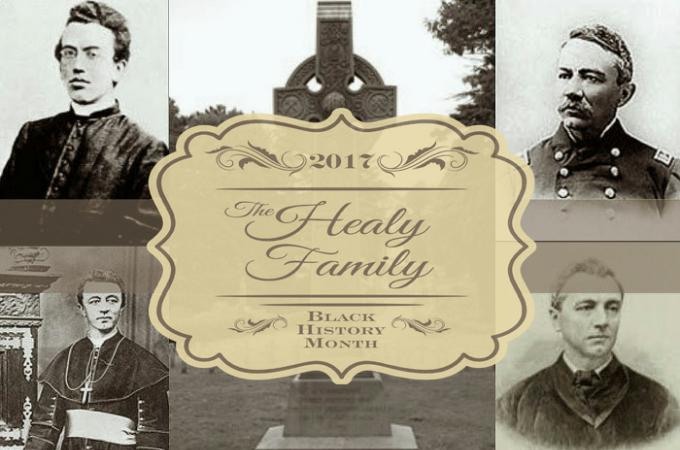

Marking Black History Month, we present the final installment of a three-part series exploring the life and legacy of America's first African-American bishop, Bishop James Augustine Healy, and his family.

Most accounts of the Healy family have focused on the brothers, and this is perhaps understandable. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was men who were presumed to do the things of which history rightly took notice. But despite the presumptions that limited the roles of women in society, the three sisters in the family are equally worthy of attention. Unfortunately, no photographs survive for any of them, but we can still know much about them.

Martha Ann was the oldest, born in 1838. She could not follow her brothers to Holy Cross, since the school enrolled only boys. But she did join them in Massachusetts, boarding at first with the Boland family of Cambridge, the sister and brother-in-law of Bishop John Fitzpatrick. She was truly a member of the family. During one Christmas vacation from college, the boys visited from Worcester, and James described in his diary the holiday revelry: up early for Christmas Mass, an afternoon sleigh ride, toasts of "egg-nog," and some horseplay during a gift grab-bag in which one of the youngsters almost hit the bishop on the head with a cane.

Like the others, Martha needed formal education, and this was arranged under Church auspices. In 1849, James became a student in the Sulpician seminary in Montreal, a place where many young men from the United States studied for the priesthood. Located almost directly across the street from this institution was a convent and school of the Congregation de Notre Dame, and a year later Martha (age 12) became a student there. Distinct from other orders which bore the "Notre Dame" designation, this group of sisters had been in Canada since the 1600s, and the education they offered young women was among the best. The normal language of instruction was French, and students pursued academic subjects, together with lessons in music and art. Unusually for the time, the school also promoted "physical culture" (that is, regular exercise) among its pupils.

So much was Martha a part of the school that she decided to join the Notre Dame congregation, and she enrolled as a novice. But after a few years, she decided that the life of a religious sister was not for her after all, and she returned to Boston, where James and Sherwood were now serving as priests. There she met an immigrant store clerk named Jeremiah Cashman, whom she married in 1865, thereafter living in comfortable, middle-class respectability in Newton and Waltham. Her descendants form the line of the Healy family that still survives today.

Martha's younger sister Amanda Josephine (born 1845 and called "Josie" by the family) joined her at school in Montreal. After a few years, she decided to join a different religious community, the Religious Hospitallers of St. Joseph, a nursing order. These sisters staffed the famous Hotel Dieu, long established and by the 1870s pioneering such medical techniques as sterile operating theaters and even private rooms for patients. The life of a nursing sister was always busy, as she explained in a letter to her brother Patrick at Georgetown. Her daily routine: up at 5 a.m. every morning for an hour of prayer; then "service to the poor" in the hospital wards; the sisters' own meals squeezed in when possible; very little chance for "recreation," which usually meant a simple walk outside. The rigor took its toll, and after just a few years Josephine died, only 34 years old.

Eliza Healy, named after her mother, pursued a similar path as her sisters. She joined the Notre Dame Congregation in Montreal and had an extensive career of teaching and administration in their schools in Canada and the United States. The order was expanding rapidly, renowned for giving its students "the most comprehensive education that persons of better quality could desire." Her longest assignment was as principal of a girls high school academy in St. Albans, Vermont, but she also helped found schools on Staten Island, New York, and in several Canadian towns. Though women of her era were unlikely to have professional careers, she found in religious life the opportunities to have an enduring impact on her students and the communities in which they lived.

The achievements of the three Healy sisters, personal and professional, together with those of their brothers, confirm that this was by any reckoning a remarkable family. Redoubling that accomplishment were their mixed race origins. Throughout their lifetimes, society would have defined them as unalterably African American and therefore precluded from anything but a life of exclusion and discrimination. They simply ignored those supposedly iron-clad rules and built their own lives of success, aided by the Catholic Church. For that reason, they are worth remembering, not just during Black History Month, but throughout the year.

- JAMES M. O’TOOLE IS THE CLOUGH MILLENNIUM PROFESSOR OF HISTORY AT BOSTON COLLEGE. HE IS THE AUTHOR OF “PASSING FOR WHITE: RACE, RELIGION, AND THE HEALY FAMILY” (UNIVERSITY OF MASSACHUSETTS PRESS, 2002). HE IS CURRENTLY COMPLETING A NEW HISTORY OF BOSTON COLLEGE.