Harrison Butker and JPII on the dignity and vocation of women

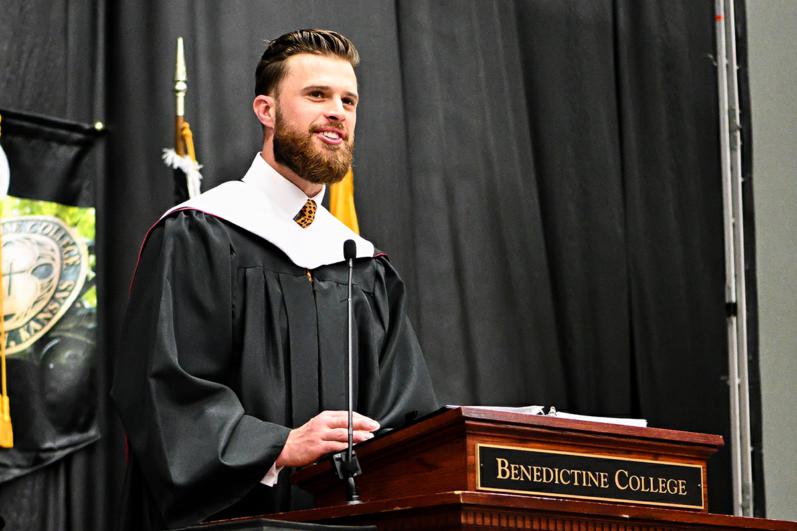

There is little needed to set fire to the world of online Catholics -- and last week's commencement speech from Kansas City Chiefs kicker Harrison Butker to an audience of Benedictine College graduates seemed to riddle Catholic social media with fractures, as traditionalists and liberals, Catholics and non-Catholics, and even men and women came to loggerheads over how to digest the controversial remarks.

The real tragedy may be, though, that lost in the greater discourse is how many of Butker's beliefs are not those of the Catholic Church at large -- certainly Natural Family Planning is not simply a form of "Catholic birth control," and priests are not called to live lives set apart from their flock, both things Butker suggested. Butker's apparent vision of the role of women in society, while not entirely incorrect, is an overly simplistic version of the Church's own vision, which is rich, nuanced, deep and beautiful. And not centered on biological motherhood alone.

Butker's remarks, in context, suggest that while the women in his audience had achieved great things, they had done so under the auspices of a "diabolical lie," which led them to seek corporate achievement instead of a life in the home.

"Congratulations on an amazing accomplishment," he said to the women in the audience, before suggesting that they have "had the most diabolical lies told to you." While they may go on to "successful careers in the world," he suggested his wife's life only "truly started when she started living her vocation as a wife and as a mother."

As Catholics, we see a difference between a job and a vocation -- the latter being a call from God Himself, and a purpose for life that aligns with God's plan. For many women, including myself, our vocation includes marriage and biological motherhood. For many women, it is a call to holiness, to chaste singleness or to the acknowledged highest calling of a woman, religious life.

Butker's comments, many Catholic and non-Catholic women believe, suggest that he believes the role of a stay-at-home spouse to be the highest, if not the only legitimate calling, for women -- or at least, as Emily Stimpson Chapman smartly noted in her own essay earlier this week, many women who are familiar with online Catholic traditionalists and the so-called Man-o-sphere interpreted it that way.

Whether that was Butker's intention or not, his remarks, and perhaps his beliefs, seem poorly constructed in light of Catholic social teaching, articulated so boldly in St. John Paul II's work on the subject of the vocation of women, "Mulieris Dignitatem."

Popes have spoken only infrequently on the subject of women's roles in society. In the 1500s, the Catechism of the Council of Trent suggested women should remain at home, exiting to the outside world only with their husband's permission.

The Church is largely silent again until the early 20th century, when Pope Pius XI authored "Casti Connubii," "Of Chaste Wedlock," which gave passing thought to women as keepers of the home, among its more strident proclamations on abortion, birth control and the sanctity of marriage.

Pope John Paul II, however, devoted an entire apostolic letter to the subject of the dignity and vocation of women in the early 1980s -- at a time when women were moving in large numbers into the working world, and feminism was well within its third wave. But his words are not designed to chastise women, but to remind them -- and society at large -- of the significant and, more importantly, vital role that women play in the world, not just as biological mothers, but as spiritual, societal, temporal mothers as well.

Many protestants -- particularly those who have built careers and followings off of the idea of "Biblical Masculinity" -- may view women as subservient to men from the beginning. Pope John Paul II entertains no such thought, elevating instead the "mutual relationship" of man and woman in marriage, and noting that "domination" of either sex threatens civil stability. To find inequality and enmity in the relationship between men and women not only disadvantages women, subjecting them to all manner of crimes against dignity, but it also "diminishes the true dignity of the man," as it goes against the ethos "which was originally inscribed by the Creator in the very creation of both of them in his own image and likeness."

Women, he says, are different than men -- significantly so -- but no less made in His image.

Even Jesus Christ, Pope John Paul II notes, exhibited no qualms about speaking frankly to and with women -- a rarity in Jesus' time -- and that the "order of love in the created world of persons first takes root in a woman." Mary, the mother of Christ, is intensely maternal, undoubtedly the paragon of femininity, and it is her free will assent to God's purpose for her life that ushers in salvation, "impossible with men, but not with God."

There is no doubt God believes women have dignity and that they are made in His image, but what of their vocation? Pope John Paul II speaks to that, as well, in depth in his apostolic letter where he lays out the several callings given to women and how both biological and spiritual motherhood are consequential and necessary -- but it is perhaps his Letter to Women in 1995 that puts it more concisely.

In this letter, Pope John Paul II calls upon women to participate in "every area of life -- social, economic, cultural, artistic, and political," and he suggests that a "greater presence of women in society will prove most valuable," for "it will help to manifest the contradictions present when society is organized solely according to the criteria of efficiency and productivity, and it will force systems to be redesigned in a way which favors the processes of humanization, which mark the 'civilization of love.'"

His words get to the heart of how the Church views women. While traditionalists, conservatives and often Catholics, may be tempted to dismiss "feminism" out of hand, Pope John Paul II reminds us that women are in fact equal in dignity and called to all sorts of vocations and involvement. Their womanhood, their feminine genius and their maternity -- things often seen as weaknesses by radical and secular feminism -- are, in fact, strengths. Women, by their very maternal nature are assets to every part of society, as long as we don't deny our female nature, but embrace it.

Although biological motherhood and stay-at-home parenthood are perfectly wonderful -- and perhaps among the most vital -- vocations, Pope John Paul II and the Church, are clear: the "diabolical lie" is not that women are meant to be in the corporate world, but that their womanhood does not matter in the corporate world.

The "diabolical lie" of feminism is that women have nothing unique to offer to society that differs from what men offer, rather than assets, intrinsically linked to their womanhood, that make them essential to every area of life.

We can't reduce Catholic thought on how women do that to a shallow, bumper-sticker observation on a single woman's vocation, nor can we say that "life" begins for women when they become wives and mothers. Certainly, for me, despite years in the workforce, and my position writing to you now, raising my children remains the most significant job of my life. It is, as many women know, the greatest job I could have hoped for.

But that is not to say that my life only began at their birth. As humans, made in the image of God, our lives begin the moment we come into existence as an individual thought of our Creator, and there are as many plans, purposes and vocations as there are people.

That is, of course, very hard to fit in a commencement speech.

EMILY ZANOTTI IS A HUMOR WRITER AND POLITICAL COMMUNICATOR WHO FOCUSES ON THE JOYS AND TRIALS OF LIFE AS A CATHOLIC MOTHER. SHE LIVES IN NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE WITH HER HUSBAND, THREE CHILDREN, TWO CATS AND FOUR CHICKENS.