Culture

The letter continues discussing some personal matters one might not expect from a young student writing his bishop during this era.

Lester

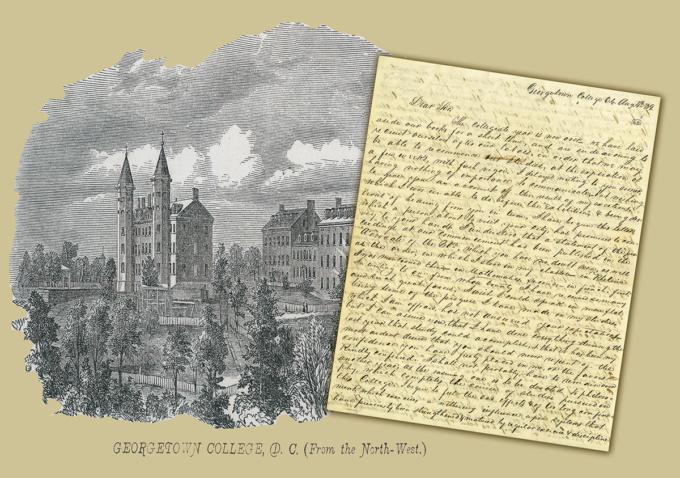

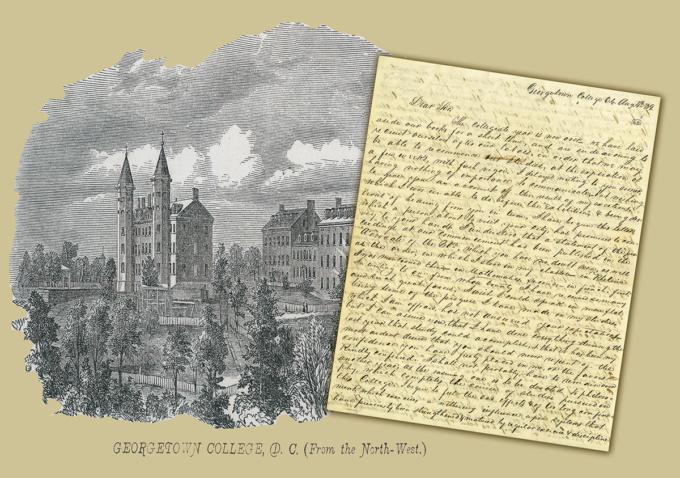

On Aug. 4, 1839, Joseph Ringe, a Maine native, took time to write Bishop Benedict Fenwick of Boston at the start of his summer holiday at Georgetown College.

The school year had just ended. Final examinations took place at the end of July each year. So, a few days later, he begins his letter stating, "the collegiate year is now over," and he and his classmates "have laid aside our books for a short time, and are endeavoring to recruit (sic.) ourselves after our labors, in order that we may be able to recommence our studies at expiration of a few weeks with fresh vigor."

Ringe apologizes for not writing the bishop sooner but, having already communicated the "result of my exertions," he did not have anything else of consequence to report. He was writing now because he met someone traveling to Boston who would convey the letter there. He adds that, while he expects Bishop Fenwick has learned about the college's commencement from a college publication, he reiterates that he came third in his class in Rhetoric, second in Mathematics, and first in French the previous year.

Despite this impressive achievement, he expresses fear that he has not met the expectations of the bishop who has been so supportive of him, though he expects that, at his current rate of progress, he will graduate at the conclusion of the next school year.

The letter continues discussing some personal matters one might not expect from a young student writing his bishop during this era. An air of melancholy surrounded Ringe. His "confinement" at the college has sapped his physical strength and mental acuity, he reveals. "You are well acquainted with the dimensions of our contracted play-ground," he writes Bishop Fenwick, "to which we are confined the whole year, both when there is school and when there is not."

Indeed, the published rules of the college stated that students were only permitted to leave the college once per year, regardless of the duration of their absence. Students whose families lived near the college were permitted to visit once each month but had to return before nightfall the same day. The rules state that "experience has proved that mere complimentary visits have given occasion to disorders: no student, therefore, will be allowed to visit any person except his parents or legal guardian."

Ringe continues to discuss his health and that the bishop "must be conscious . . . Of the necessity boys are under to taking full and vigorous exercise," which promotes health and, in making the body strong, renders the mind active.

He has a fear that he may die of consumption and periodically feels pressure in his chest, making him averse to the excursions of sports which the students generally play. Instead, he finds that swimming in the Potomac River each evening delights him, provides the activity he craves, and gives him time for contemplation. "When buffeting the waves," Ringe writes, "I imagine that the waters present me with a fit emblem of the tide of life, pertinaciously closing around us to obstruct our passage, but yielding continually to the action of our arms, 'till finally we receive a way has been opened by our strenuous exertions."

Ringe continues that of about the 150 students enrolled in Georgetown College, only about 40 remained during the summer holiday, all of whom "appear quite discontented, and some, even miserable." He reveals he has had periods of melancholy and is unhappy because all his friends departed for home, either graduated and never to return, or until the new year was due to start in mid-September, leaving him feeling stranded.

A few friends invited him to their homes, most of whom lived along the Potomac, either for the entirety of the holiday or to join them at some point, but he declined, wishing to first write Bishop Fenwick for permission, and "whose decisions I shall await with due deference and respect."

In the meantime, he moves on to discuss a Sister Claudia whom they both know, and then speaks of the literary society which had been formed to help its members "acquire the habit of expressing their ideas with cogency and effect." Most of the debates were on literary topics, politics were forbidden. Members kept asking if they could put forth his name as a new member, and Ringe states he has had to "resort to every excuse I could devise" to avoid it. Again, he would like the bishop's direction as to whether or not he should join.

According to a centennial history of Georgetown College, Joseph Ringe, listed as Joseph Rindge, did indeed survive the long summer holiday and graduated the following year.

- Thomas Lester is the archivist of the Archdiocese of Boston.

Recent articles in the Culture & Events section

-

Building a legacyMichael Reardon

-

Scripture Reflection for Nov. 24, 2024, Solemnity of Our Lord Jesus Christ, King of the UniverseDeacon Greg Kandra

-

Seeds of graceMolly M. Wade

-

The dedication of St. Francis Chapel in the Prudential CenterThomas Lester

-

Honeybees are taking over for canariesDeacon Timothy Donohue